|

|

Christi Belcourt encourages viewers to notice details, objects, and events whose worth and importance are often belied. To this end, she uses the bead, an object insignificant in size and simple in design, as the foundation of her art. Through the bead, Belcourt is connected to her Métis heritage and its artistic traditions. The Métis, a new people that arose when First Nations and European traders in North America formed alliances, were instrumental in shaping Canada as a nation. Their roles as trappers, traders, guides, farmers, and political leaders helped establish the Canadian economic and political structure.1

The Métis' emerging cultural identity was solidified by a strong aesthetic vision expressed through the embellishment of a myriad of functional objects with intricate and colourful designs. Items as diverse as gun cases, moss bags, clothing, pouches, and dog blankets, were turned into things of beauty. The Métis were skilled in silk embroidery, quill work, and moose hair tufting but beadwork became their preferred form of art. 2 They developed their unique and distinctive floral patterns, prompting other First Nations to call them the "Flower Beadwork People". Their beadwork emphasized symmetry, balance, and harmony in patterns extracted from nature and from the models of European lacework and church decoration.3

Belcourt takes the diminutive bead and transforms it into large acrylic landscapes and beadwork images inspired by the principles of Métis art. She simulates the appearance of beading in her canvases by dipping the end of a paintbrush, or a knitting needle, into paint to create tiny dots. Belcourt also finds sources of inspiration in the work of Woodland School artists like Norval Morrisseau and Blake Debassige. Morrisseau, the Woodland School's best-known exponent, adapted the iconography of Ojibway sacred scrolls, pictographs, and beadwork to create paintings and prints. Woodland art is notable for its use of black outlines and solid blocks of colour to render figures and shapes in a bold linear style.4 Belcourt's concentration on landscapes and floral designs, absent of human or other figures, separates her work from the Woodland School.

Belcourt's appreciation of the diversity, complexity and beauty of plants has led her to study them in detail and, consequently, given her a keener understanding of their relationship to the larger environment. It has made her aware of the potential healing powers and medicinal components of plants, including those most people would consider weeds. She draws an analogy between weeds, generally ignored or destroyed, and the Métis, known also as the Forgotten People, who were pressured to abandon their identity and way of life. Métis political and cultural issues are threaded throughout her work, as well as a concern with the welfare of humanity as a whole. Belcourt explains that:

"The plants within my paintings have become metaphors to parallel our own lives. The roots show that all life needs nurturing from the earth to survive, and represent the idea that there is more to life than what is seen on the surface. It also is to represent the great influence our heritage has over our lives. The lines which connect the plants symbolize our own interconnectedness with each other and all living things within Creation. The flowers and leaves reach upwards as we seek out our individual spirituality and look to our uncertain future."

The spiritual aspect of her art also manifests itself in her the great patience and rhythmic application of paint her working methods demands. While she paints, Belcourt listens to music - jazz, old time country, and urban folk - that seeps into her consciousness. Belcourt's spiritual relationship with nature was renewed when she moved to a rural area in the LaCloche mountain range near Manitoulin Island in Ontario. This move corresponded to a shift Belcourt made in her professional life - leaving employment as a communications officer with the Métis National Council to embark on a career as a full-time artist. Belcourt's interest in art has always been strong, she has been painting since the age of fifteen, but her decision to change the direction of her life sprang from an encounter with a fellow artist: "In 1997, I had the privilege to hear renowned artist Daphne Odjig speak at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery. She spoke of taking the ultimate leap from painting part-time to painting full-time. Her advice to upcoming artists was to 'take that step, jump in with both feet, otherwise you may never know if you could make it.' These are words I took to heart and have lived with every time I put a paintbrush in my hand."

Another pivotal figure in the evolution of Belcourt's life is honoured in The Conversation (2002). This painting uses beadwork imagery to pay tribute to the memory of Yvonne McRae, a close friend and important mentor to Belcourt. Friends of McRae commissioned the painting for the Thunder Bay Art Gallery's permanent collection because she spent many years in Thunder Bay and, Belcourt reveals, her connection to the city remained strong even after she moved to Ottawa.

The Conversation (2002) dotted floral pattern on a black background symbolizes nineteenth-century Métis beadwork on black velvet. The image, with its tendrils and leaves radiating out from a large red flower, brims with life and vitality despite its controlled design. Belcourt entitled the painting The Conversation because,"Yvonne was the kind of woman who when you were in her presence you felt instantly at ease. She had a way of bringing out the best in you. Everyone who knew her would enjoy the most wonderful and interesting conversations with her during visits that would last for hours and hours." The central flower represents McRae as well as our shared spirit while the intertwining plants, which almost overflow the picture space, indicate McRae's ability to connect and embrace people. McRae was originally from Manitoulin Island and, in recognition of her heritage, Belcourt has selected traditional Anishnaabe beadwork colours for the flowers.

Resilience of the Flower Beadwork People (1999) the earliest painting in Lessons from the Earth, is a Woodland-influenced landscape that illuminates some of the key ideas Belcourt explores in her art. The title is a reference to the Métis' survival despite an often hostile political and social environment that has included government appropriation of traditional Métis land and a refusal to recognize the Métis as a distinct people. Belcourt says that, "We have survived through incredible odds. We were a new nation being born, as Canada was being formed. We very easily could have been absorbed into the mainstream society. The pressures were there from all sides encouraging this to happen. And certainly in a lot of cases, we have been forgotten to this day. No matter. We are here."

The painting focuses on the strength of the Métis despite the hardships they've endured. The image features brilliantly hued purple, orange, and blue flowers against a soft yellow background. The black of the stems, roots, and outlines contrast strongly with the background and give the image a flat linear appearance that is characteristic of Woodland School art. Dots of paint adorning the plants incorporate beadwork motifs. The two halves of the painting are mirror images of each other and the eye is led to the centre of the canvas by two identical plants that flank a much smaller, less noticeable plant with a blue flower. Belcourt explains that, ". . . the Métis are represented by the blue flower in the centre. The other flowers represent the many different Aboriginal nations, of which we are one. Yet we stand out, we are unique among our brothers and sisters. . . I also see it as all the flowers representing the diversity within our Métis Nation. We have so many heritages - Cree, Ojibway, French, Scottish, English, Chippewa, Dene, Irish, Mohawk and so on. Yet we can still grow alongside each other, roots entwined, and call ourselves Métis"

The vividness of the flowers evokes the presence of spring with its connotations of hope and resilience. This impression is intensified by the appearance of the blossoms of many different flowers on a single plant. The painting captures the burgeoning strength of the Métis between the established plants symbolizing the Europeans and First Nations. Belcourt's magnification of the plants forces the viewer to become aware of their character, structure, and individuality. It is impossible to overlook them as they are often overlooked in everyday life.

The Metis and the Two Row Wampum (2002) enlarges on the theme of the birth of the Métis Nation and their place in Canadian history. Painted entirely in dots, this work has dramatic colours and a dynamic design. The interplay of the black background and the sinuous white stems animate the image and imparts a strong sense of movement. The colourful flowers springing from the stems further enliven the composition. These stems symbolize the agreements, memorialized in wampum belts, reached between First Nations and Europeans to live peaceably with each other. Belcourt has chosen to make the stems undulating because, ". . . at the time of the creation of the belts, there was no way to foresee the history in Canada that was to unfold - that the Métis would emerge as a unique People. . . The blooming flowers and growing stems represent the birth of the Metis Nation out of these two worlds, and the continuing reality of Métis existence in Canada." The large pink and green rosettes detached from the stems and floating on the black background create a second focal point that alludes to the Europeans and the First Nations.

Belcourt's desire for viewers to fully understand the painting, as well as to experience the intimate relationship between beading and the human hand, has led her to invite them to run their fingers over the raised dots of the stems. Such an act will allow viewers, "to touch the past," and by doing so draw into question events in Canada's history and how they relate to our existence today."

Medicines to Help Us (2003) focuses on the present rather than the past in its consideration of the obstacles faced by the Métis in the contemporary world. The painting is, in several ways, a stylistic and thematic culmination of Belcourt's work to this point. The image unites Belcourt's beadwork and landscape paintings by combining the black background of her beadwork canvases with the imagery and style of her landscapes. The work once again identifies the Metis with wild flowers but Medicines to Help Us diverges from Belcourt's previous work in the portrayal of actual rather than imaginary plants or amalgamations of multiple plants. Some of the twenty-seven plants depicted include Yarrow, Blueberry, Stinging Nettle, and American Ginseng. The presence of so many plants in a single canvas gives the painting a rich tapestry-like effect. Belcourt describes the work as:

". . . a painting for the Métis Nation. Each plant depicted is a type of wild plant that can be found in one or all provinces from Ontario to British Columbia (the same area of land as the traditional Métis homeland). Some of the plants are indigenous to North America . . . and some are introduced species from Europe but also have been used by Indigenous people for medicines . . . The medicines and plants in this painting are my prayers for the Métis Nation to encourage our healing . . ."

The painting invites quiet contemplation as viewers are drawn into and absorbed by the study of individual plants. Maple leaves, the symbol of Canada, leap out from the centre of the image. They also appear on the left and right sides of the canvas. Their presence suggests that the Métis are an integral part of this country and its history.

Tolerance and respect are some of the fundamental lessons that Belcourt has learned through her study of nature and they are lessons that she wishes to teach people through the medium of her art. The coexistence of a multitude of plants in the natural environment, each with their own unique beauty and healing powers, points the way to a more just world in which diversity is honoured and the Forgotten People and their contributions are recognized.

Tracey Henriksson, Curator

Information about the artwork was gathered from conversations and correspondence with Christi Belcourt.

NOTES

1. Métis: A Glenbow Museum Exhibition (Calgary: Glenbow Museum, 1985).

2. Ibid.

3. Jacqueline Peterson and Jennifer S.H. Brown, The New Peoples: Being and Becoming MÈtis in North America, Manitoba Studies in Native History I (Winnipeg: The University of Manitoba Press, 1985).

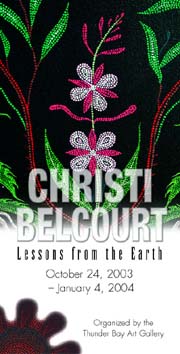

Lessons from the Earth is an Enlarging the Circle exhibition organized by the Thunder Bay Art Gallery, 24 October, 2003 - 4 January, 2004.

|

|

"We

are resilient as a weed and beautiful as a wildflower. We have much

to celebrate and be proud of."

"We

are resilient as a weed and beautiful as a wildflower. We have much

to celebrate and be proud of."